History of Kathak

Kathak, derived from the Sanskrit words 'katha' (story) and 'kathakar' (story-teller) is the classical dance form of the Indo-Gangetic belt. It is rooted in Brahminism when the Brahmin priests of the temples recited and enacted stories as the priests reached a state of rhapsody. Thus the seed of the dance form lies in the accompanying gesticulations and mime that became evident in the visual discourse/ sermon being delivered by the Brahmin priests while recounting mythological and moral tales. Thus they formed the 'dharaka' stream of kathaks as against the 'pathak' stream. By 4th century BC, it had evolved into a high state of fine art as is evident from the Prakrit verse of that period.

The earliest reference to this community is found in two Mauryan period epigraphies: (a) a Prakrit verse from 4th century BC describing the dance of the Kathaks on the banks of the Ganges at Varanasi that pleased Lord Adinath; (b) the 3rd BC verse 'nrittadharmam kathaakaaccha devalokam' (Gangetic belt). The three references in the great epic Mahabharata, the Adiparva (viz. 'kathakasca rajan shravanasca vanaukasah divyakhyanani ye ca'pi pathanti madhuram dwijah'), the Anusasana parva and the Sabha parva are indicators to the well over 2500 years long history of the Kathaks.

During the medieval period of Indian history, it saw formalization and stylization, reaching unprecedented heights in sophistication. This period also saw furtherance and efflorescence of rhythmic parameters of the dance form while retaining its Hindu devotional flavour. The Vaishnavite movement which swept North India after 10th century and the resultant Bhakti movement contributed to a whole new range of lyrics and musical forms. The bhakti movement brought in an element of romanticism. Portrayed through the popular tales of Radha and Krishna reflected in the works of Mirabai, Surdas, Nandadas, Krishnadas etc, human emotions of devotion, yearning, sorrow and joy were given prominence. In addition the earlier prevalent Shaivite and Shakti themes continued to flourish. During the medieval period of Indian history, the Mughal era saw yet another facet of formalization and stylization of the dance form in the hands of the traditional male Brahmin Kathaks. Mimetic sequences always centering around Hindu mythological tales saw varied interpretations.

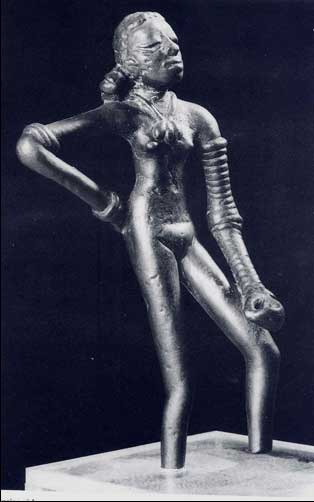

Natural movements, intricate rhythmic patterns, controlled vitality, complicated footwork, breathtaking pirouettes and heart rending mime are the hallmarks of Kathak. It subtly explores a range of moods with delicacy and balance, extending the limits of arts representing a grand 'plurality' so quintessential to Indian philosophy. Its basic 'samapada' stance enables a Kathak to perform from the slowest of tempos ('ati-vilambit') to the fastest of speed ('ati-drut') while also enabling riveting long sustained pirouettes and sparkling footwork. All tenets of Natyashastra are reflected in the dance form, be it in the 'abhinaya', the 'gat nikas' reflecting 'charis', 'bhramaris'(pirouettes), 'mandalas-sthanas', 'karnas', or the 'gat-bhavas' that reflect the 'mandalas-charis-mudras' et al. As 'kathak' or storytellers, 'abhinaya' (mime-expression) is its soul. Keeping intact the legacy of its origin, Kathak is the only dance form where the dancer 'narrates' and 'enacts' till today.

Philosophy of Dance

Kathak to Shovana has been her breath, her life and her passion. Even at the very young age of 'not yet three', Kathak meant a whole range of emotions and rhythms, reflective of life itself. Kathak gave her praxis, sense of balance, helped her hone the sensibility that was part of her family background and upbringing, contributing to her health and identity. It helped her to know and discover her roots and yet appreciate all cultures of the world. Shovana strongly believes that its strength lies in its inherent nature of being inter-disciplinary that imparts to it the virtues of being socio-historical, cultural, biological, psychological and metaphysical. Dance, especially classical dance, imparts a balance between the 'yin' and the 'yang', between the 'tandava' (violent) and the 'lasya' (graceful) emotions present within each one thus exhibiting the highest form of 'yoga' with a sense of balance and harmony between the physical, spiritual and mental. Dance, to her, is a two-way dynamic exchange between the world and the active perception of the dancer.

Shovana Narayan

Shovana Narayan  Mob: +919711543781, +919811173734

Mob: +919711543781, +919811173734 Email :

Email :